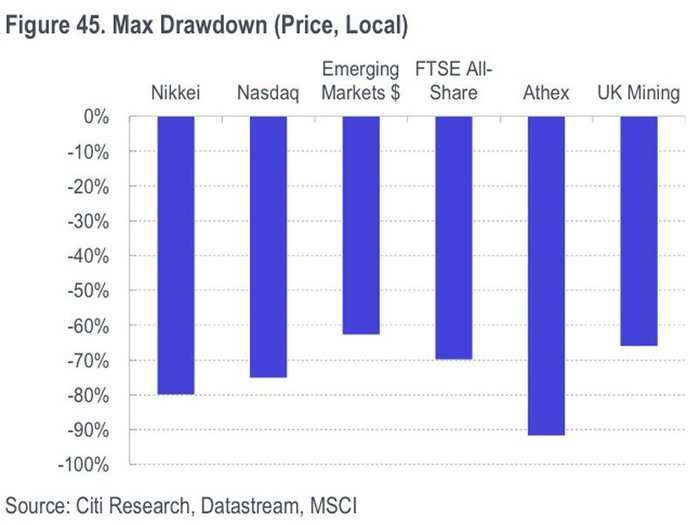

"Figure 45 shows various markets and industries which have suffered severe losses in relatively short order in recent decades, e.g., the UK (1972-74), the Nasdaq (2000-03), Greece (2008-12) and Mining (2008-09),"Citi's Jonathan Stubbs wrote.

"Hence, buyer beware."

“Despite average intra-year drops of 14.2%, annual returns positive in 27 of 36 years,” JP Morgan Asset Management’s David Kelly observed.

"Since 1926, the average annual return for US stocks has been a little more than 10%, and this seems to be pretty common knowledge for even neophyte investors," Vanguard analyst Donald Bennyhoff wrote. "So 10% would seem to be a reasonable expectation for an average year, right? Our illustration ... shows how often that assumption is erroneous, but it is also irrelevant."

"We find no relationship between historical five-year returns and subsequent 12-month returns," Bank of America Merrill Lynch's Savita Subramanian wrote.

Using some simple regression analysis, she found an R-square of 0.0002. That's about as low as R-square gets. (R-square is a statistical measure that reveals how well a regression line — the line of best fit you see — explains the relationship between two variables. The higher the R-square, the better that relationship is explained.)

See also: "These 0s prove past performance is no guarantee of future success"

"While the bottom-up EPS estimate declined during the fourth quarter, the value of the S&P 500 increased during this same time frame," FactSet's John Butters observed. "From September 30 through December 31, the value of the index increased by 6.5% (to 2043.94 from 1920.03). This marked the 14th time out of the past 20 quarters in which the bottom-up EPS estimate decreased while the value of the index increased during a quarter."

"Our work suggests that valuation is a poor short-term timing indicator, but the single-most important determinant of long-term returns," Bank of America Merrill Lynch's Savita Subramanian said.

"Valuations have historically explained 60-90% of subsequent returns over a 10-year horizon. Normalized P/E – our preferred valuation metric – has explained 80-90% of returns over the subsequent 10-11 years."

See also: "Everything we know about PE ratios crammed into a useful, yet somewhat confusing chart"

"[W]e have found that the average P/E at the end of prior bull markets has fluctuated rather significantly, averaging 18.4x but with a standard deviation of 5.4x," BMO's Brian Belski observed. "This suggests to us that valuation by itself is not reason enough for a bull market to end."

"We admit that historically a high Shiller P/E has often resulted in subsequent negative returns; however, this has not always been the case and there are several examples where subsequent 3-year returns surpassed 20%," Credit Suisse's Andrew Garthwaite said.

Using a hundred years' worth of Shiller's data, Garthwaite charted the observed three-year forward returns for various levels of Shiller's PE. The red rectangle sums up the observed three-year forward returns when the PE was at levels not long ago.

Currently, Shiller's PE is at 24.1, which in the past has seen returns above 20% and worse than -30%. Some returns were just lackluster. Indeed, the range of returns is very wide. In other words, the signal is very ambiguous.

On the left, you see the historical one-year returns on the S&P 500 at various levels of the forward P/E. As you can see, the observations are scattered. There've been times when the market has been very expensive, yet delivered huge one-year returns. There've also been times when the market's been cheap, yet delivered crummy returns.

Bottom line: The popular forward P/E is terrible at predicting what the market is about to do.

However, don't ignore the chart on the right. It plots the five-year returns at those same historical forward P/E levels. As you can see, when you extend the holding period, the forward P/E becomes a more reliable metric.

So we're left with two lessons: 1. Don't rely on forward P/E to make short-term trades in the market, and 2. Be patient in your investing strategy, because theory and practice are more likely to align if you're in it for the long term.

"Buying stocks with high PE ratios has not been a good strategy," Barclays Jonathan Glionna observed.

Figure 14 shows the performance of a strategy that went long stocks with high PEs and short stocks with low PEs. Over the last 25 years, that strategy would have resulted in substantial losses. Overall, we believe high revenue growth strategies should be pursued with a cautious approach and not chased when the price is high – as it is now."

BMO's Brian Belski recently reminded clients that a bout of weakness and volatility fits into the narrative of long-term, secular bull markets.

“[I]t is important to note that the market has entered a secular stage where shorter-term volatility tends picks up, particularly considering how long the market has gone without exhibiting a major correction,” Belski said. “Therefore, even if market struggles persist or enter outright ‘bear market territory’ over the near term, we believe it should have no impact for those investors with a longer-term focus."

This chart of the current cycle (dotted red line) is overlaid with the average trajectories of the last two secular bull markets (solid blue line). Note the big dip in the blue line after year five. That's Oct. 19, 1987, the day the Dow plunged a breathtaking 22% in one day.

"We compare a buy-and-hold strategy vs. a panic selling strategy from 1960-present," Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s Savita Subramanian wrote. "We assume an investor sells after a 2% down-day and buys back 20 trading days later, provided the market is flat or up at the end of that period."

Can you guess what happened?

"This strategy underperforms the market on a cumulative basis since 1960 both overall and during every decade, given the best days typically follow the worst days."

See also: "If you missed the rally, then you probably just made the most classic mistake in investing"

And: “Here's the smartest way to invest in stocks if you're convinced the market will keep crashing”

Bank of America Merrill Lynch's Subramanian shared a chart that does a nice job of illustrating the roller-coaster ride that stock market investors actually experience.

She reviewed 12 major S&P 500 peaks since 1930 and averaged the price performance during the months leading into the peak and the months after.

To be clear, this is just a summary of what has happened in the past around market peaks. In between these events are long periods of lackluster action in the markets. Having said that, there are a couple of things to take away from Subramanian's research:

Returns are very strong in the months leading up to a peak. The median returns in during the six months and 12 months before a peak were 14% and 21%, respectively. An investor seeking gains probably wants to be part of that action.

Declines after a peak are bad, but they don't offset the gains. The median returns in during the six months and 12 months after a peak were -12% and -15%, respectively.

But even after the violent sell-offs, markets recover losses in two years. The median return 24 months after a peak is -1%, meaning that most of the losses seen in the six-month and 12-month periods are recovered for patient investors. If anything, downturns areopportunities for investors to buy more and lower their average costs.

I spent $2,000 for 7 nights in a 179-square-foot room on one of the world's largest cruise ships. Take a look inside my cabin.

I spent $2,000 for 7 nights in a 179-square-foot room on one of the world's largest cruise ships. Take a look inside my cabin. Colon cancer rates are rising in young people. If you have two symptoms you should get a colonoscopy, a GI oncologist says.

Colon cancer rates are rising in young people. If you have two symptoms you should get a colonoscopy, a GI oncologist says. Saudi Arabia wants China to help fund its struggling $500 billion Neom megaproject. Investors may not be too excited.

Saudi Arabia wants China to help fund its struggling $500 billion Neom megaproject. Investors may not be too excited. Catan adds climate change to the latest edition of the world-famous board game

Catan adds climate change to the latest edition of the world-famous board game

Tired of blatant misinformation in the media? This video game can help you and your family fight fake news!

Tired of blatant misinformation in the media? This video game can help you and your family fight fake news!

Tired of blatant misinformation in the media? This video game can help you and your family fight fake news!

Tired of blatant misinformation in the media? This video game can help you and your family fight fake news!

Copyright © 2024. Times Internet Limited. All rights reserved.For reprint rights. Times Syndication Service.