9 Ways To Observe And Deduce Like Sherlock Holmes

Observe the details.

Pay attention to the basics.

When Holmes famously quips that the solution of a case is "elementary," he's not simply dismissing the detective work as easy. Rather, he's talking about elements, the essentials of a situation.

Holmes says:

"Before turning to those moral and mental aspects of the matter which present the greatest difficulties, let the enquirer begin by mastering more elementary problems."

As a physicist begins with the laws relevant to a problem, a detective begins with the facts of a case before adding in interpretation.

"Whatever the specific issue, you must define and formulate it in your mind as specifically as possible — and then you must fill it in with past experience and present observation," Konnikova writes. "As Holmes admonishes Lestrate and Gregson when the two detectives fail to note a similarity between the murder being investigated and an earlier case, 'There is nothing new under the sun. It has all been done before.'"

Use all of your senses.

In the novel "Hound of the Baskervilles," Holmes assembles clues not just by reading everything he can find, but involving all his senses.

As he tells Watson:

"It may possibly recur to your memory that when I examined the paper upon which the printed words were fastened I made a close inspection for the water-mark. In doing so I held it within a few inches of my eyes, and was conscious of a faint smell of the scent known as white jessamine. There are seventy-five perfumes, which it is very necessary that a criminal expert should be able to distinguish from each other, and cases have more than once within my own experience depended on their prompt recognition. The scent suggested the presence of a lady, and already my thoughts began to turn toward the Stapletons. Thus I had made certain of the hound, and had guessed at the criminal before we ever went to the west country."

While we don't need to go and memorize the smell of 75 perfumes, Konnikova says, we shouldn't neglect our senses — since they influence our decisions in ways we don't even realize.

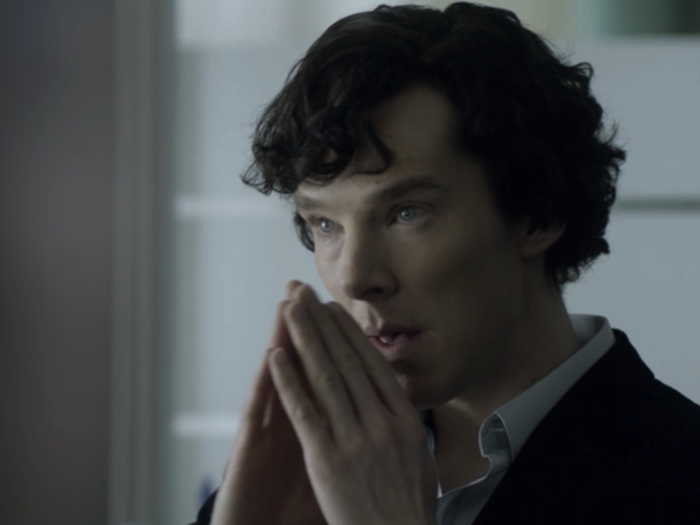

Be 'actively passive' when you're talking to someone.

When Holmes is listening to — or perceiving — somebody, he's not fussing with his iPhone.

Konnikova's take:

"Holmes ... focuses all of his faculties on the subject of observation ... He listens, as is his habit, 'with closed eyes and fingertips together.' ... He will not be distracted by any other task. As passive observers, we are not doing anything else; we are focused on observing."

Listening, we have learned, isn't just a matter of hearing the words people say. Instead, we need to attend the whole of a person's expression to get all the nonverbal information that's being communicated — but so easy to ignore.

Give yourself distance.

When Holmes is dealing with a particularly thorny case, he occupies himself with another activity, like playing the violin or smoking a pipe.

The thorniest of cases are "three pipe problems."

From "The Red-Headed League":

"'To smoke,' (Holmes) answered. 'It is quite a three pipe problem, and I beg that you won’t speak to me for fifty minutes.' He curled himself up in his chair, with his thin knees drawn up to his hawk-like nose, and there he sat with his eyes closed and his black clay pipe thrusting out like the bill of some strange bird. I had come to the conclusion that he had dropped asleep, and indeed was nodding myself, when he suddenly sprang out of his chair with the gesture of a man who has made up his mind and put his pipe down upon the mantelpiece."

Citing psych research, Konnikova contends that the pipe smoking is a way for Holmes to constructively distract himself from his thinking. In the same way that playing the violin helps the detective to sort through his thoughts, packing and smoking his pipe does his solution-finding imagination a favor by doing something with his body.

For similar reasons, we get ideas on walks.

Say it aloud.

Holmes talks to Watson about everything.

The telling helps, Holmes says. "Nothing clears up a case so much as stating it to another person."

To Konnikova, this is a fantastic device for figuring out a case:

"Stating something through, out loud, forces pauses and reflection. It mandates mindfulness. It forces you to consider each premise on its logical merits allows you to slow down your thinking."

So when you come across a particularly perplexing mystery — like how to organize a project or if you should change jobs — talking your friend's ear off about it forces you to take inventory of events, thus helping you to crack the case.

Adapt to the situation.

Holmes is not a one-size-fits-all sort of sleuth, Konnikova says. He tailors his approach to fit the case in question.

When Holmes meets a would-be source of information, he profiles him or her, looking for any advantage that might be communicated by their appearance.

He tells Watson how he nabbed details from a gambling type from intentionally losing a bet to him:

"When you see a man with whiskers of that cut and the 'Pink 'un' (a British football newspaper) protruding out of his pocket, you can always draw him by a bet ... I daresay that if I had put £100 down in front of him, that man would not have given me such complete information as was drawn from him by the idea that he was doing me on a wager."

Holmes, ever the deducer, reads people's habits from their appearance, a skill all of us can learn.

Find quiet.

If you're out there detecting all the time, you need to give yourself breaks. It's not just about getting some rest; the key is to allow your mind to filter the important observations from the inconsequential ones. Thus the need for solitude.

The importance of the aloneness wasn't lost on Watson, who writes of his friend:

"I knew that seclusion and solitude were very necessary for my friend in those hours of intense mental concentration during which he weighed every particle of evidence, constructed alternative theories, balanced one against the other, and made up his mind as to which points were essential and which immaterial."

Konnikova says that the world isn't going to quite down for you. That's why you need to seek out your own "quietness of mind," so that you can think through past actions and future plans — boosting your creativity and your sanity.

Manage your energy.

Holmes knew how to prevent the mid-afternoon dip: not to lose his energy to digestion.

Here's what he said when Watson begged him to eat:

"The faculties become refined when you starve them ... surely, my dear Watson, you must admit that what your digestion gains in the way of blood supply is so much lost to the brain. I am a brain, Watson. The rest of me is a mere appendix. Therefore, it is the brain I must consider."

For Konnikova, this evidence of Holmes' awareness that your cognitive abilities draw from a finite supply of energy, one that must, if you are to sleuth well, be managed precisely.

Now that you know how a detective thinks, see how an executive thinks.

Popular Right Now

Advertisement