The Indian tiger TRAFFIC

- Tigers, rhinos, and other populations of endangered animals in India are slowly, but steadily, recovering.

- This doesn’t mean that their quality of life is getting better, according to the head of the World Wide Fund of Nature’s (WWF) TRAFFIC network in India, Saket Badola.

- Here’s a list of animals endangered animals that are under threat from poaching primarily because of three factors — food, fashion and fun.

Earth Day 2021 is all about ‘Restoring our Earth’, and that includes the dwindling population of endangered animals in India. Some may take a sigh of relief in the fact that some populations are showing signs of increasing — like the

tigers and rhinos in India.

But, just because there are more of them, doesn’t mean that they’re doing okay. “We cannot link population increase with their overall well-being,” Saket Badola, head of the World Wide Fund for Nature’s (WWF) wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC in India, told Business Insider.

According to him, the increase is so marginal that it doesn’t necessarily indicate that everything is well with them. “Going by our observation in the field and the number of seizures we encounter, we can still say they’re in a pathetic state,” said Badola

And, this is due to three primary factors — food, fun, and fashion.

The three F’s driving illegal wildlife trade in India

TRAFFIC’s estimates show that poaching doubled during the lockdown, even though more people were supposed to be staying at home. Demand was, in part, driven by the fact that some people were either free or jobless, and therefore took up trading in wildlife as an additional source of income.

The other driver of demand was animal meat. It is the only source of animal protein in certain areas, according to Badola. Some animals are also used in the making of traditional medicines.

And, this has been a constant threat throughout the years — just like fashion.

Shatoosh shawls are made from the wool of a Tibetan antelope, fur coats or caps are made from the skins of tigers and pandas, and bags are made from the scales of pangolins and monitor lizards. These are just a few examples among a long list of how the fashion industry is part and parcel of illegal wildlife trade, according to Badola.

And, then you have fun. Exotic species, especially those in India, are targeted so that people can keep them as pets. No, this doesn’t mean people want to keep a tiger at home. But it does mean that species like parakeets, doves, turtles, and snakes are under threat.

"Wildlife trafficking is believed to be one of the major factors for pushing several species towards extinction. In monetary terms, it is the fourth biggest illegal activity across the globe," said Badola.

Here’s a quick look at the main species being targeted for illegal wildlife trade in India — and why:

Tigers, leopards, and snow leopards for their fur

TRAFFIC

"One of the main species targetted in India are big cats — tigers, leopards, and snow leopards — for their skin and bones,” Badola told Business Insider.

During the lockdown period, common leopards were either poached or their skins seized in Assam as well as Jammu and Kashmir.

Elephants for their tusks and tail hair

WWF

Ivory and elephant tail hair are the most commonly bought elephant products. For consumers, they are a symbol of wealth and power. And given their high value, the buyers are also people with significantly higher than average incomes, according to TRAFFIC.

This is despite the fact the ivory trade was banned more than two decades ago.

Unlike African elephants, only the males bear tusks within the Indian elephant population. That means poaching is skewing the gender ratio.

But, poaching is only one of many threats to India’s elephants. They’re already facing habitat loss, conflicts, and accidental deaths across railway tracks.

Rhinos for their horns

Martin Harvey/WWF via TRAFFIC

Rhino poaching is one of the major environmental issues in India’s northeastern state of Assam. The demand for their horns doesn’t come from within India but from its southeast neighbors, Vietnam and China.

Recent urban myths surrounding the medical properties of Rhino horns don’t help either. These myths claim that Rhino horns cure cancer, relieve hangovers, and enhance male virility. And, according to TRAFFIC, this is driving up demand from the average consumer.

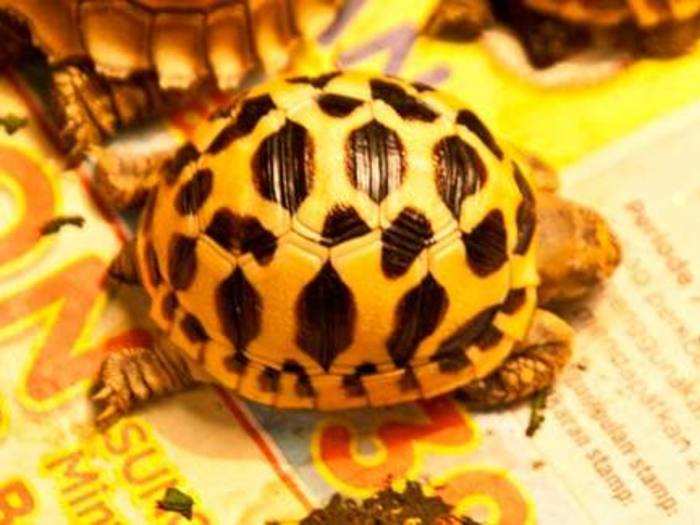

Turtles and tortoises for meat, carapace, and as pets

TRAFFIC

According to TRAFFIC, more than 1 lakh freshwater turtles and tortoises were poached illegally between 2009 to 2019. And, this may only be scratching the surface. The illegal trade watchdog claims that a large portion of the poaching goes unreported or undetected.

And, Indian Star Tortoise is one of the most demanded species on the international pet market. Despite enhanced surveillance by enforcement agencies, the trade of star tortoise continues to thrive along the foothills of the Himalayas and among the Gangetic flood plains.

Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu are one of the major regions of turtle poaching with the southern tributaries of the Ganges flowing into the ti-junction.

Over 11,000 tortoises and freshwater turtles have entered illegal wildlife trade in India every year since 2009.

Pangolins for their meat and scales

TRAFFIC

Pangolins are most likely the most trafficked mammal on the planet. This probably because every single part of the animal is in high demand — from its scales to its blood.

And, the illegal trade of Pangolins is continuing to grow despite an international trade ban all eight pangolin species that came into effect in 2017.

The population of pangolins has diminished to such a degree within Asia, that even illegal trade networks have shifted to African countries.

But, illegal wildlife trade between India, Nepal, and China continues to threaten the limited number of pangolins that are still around.

The Tibetan antelope for their wool

Rohan Pandit via WWF India

Tibetan antelopes have extremely soft, light, and warm underfur. According to the WWF, shawls made using this fur sell for as much as $1,000 to $5,000 within India. In the international market, their rates can be as high as $20,000.

In India, the shawls are in high demand as dowry during weddings. In Europe, they’re a symbol of wealth and status.

According to the WWF, as many as 20,000 Tibetan antelopes are killed each year.

Sharks for their fins

TRAFFIC

Almost 600,000 metric tonnes of sharks and rays caught each year by the world’s top 20 catchers — and India is among the top 3 after Spain and Indonesia.

Despite the fact that India banned all types of shark finning back in 2013, there are still seizures to show that illegal trade activity is ongoing.

As recently as last month, nearly 40 sharks and rays were added to the group of threatened species on the planet by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)— including one species of ray that may already be extinct.

Seashells for decoration and jewelry

TRAFFIC

The sale and collection of seashells have seen a boom in recent years. The seashell market in India is mainly driven by the demand for curious — used in making lampshades, buttons, combs, and other decorative items.

According to TRAFFIC, a sizeable about of this trade is happening on the black market. Between 2009 to 2019, over 97,000 kilos of seashells have been caught in seizures.

The issue isn’t that there is a demand for seashells, but that the demand is so high that people don’t care about destroying ocean floor beds in order to earn an extra buck.

“It leads to disruption of the oceanic ecosystem,” explained Badola. “The sheer demand for the shell is so high that in few areas it is leading to unsustainable extraction of these from the sea, resulting in permanent and irreversible damage to the local ecosystem.”