The villagers in Mokhada, in the Palghar district of India’s western state of Maharashtra, can’t help themselves.

Farmer Narayan Mahale can see the river, now drying, flowing past through the year. But that water often does not reach him. Photo: Kunal Purohit

This region is facing a crushing

Very few villages have any piped supply of water. As a result, many of them have to depend on common wells. But last year’s scarce rainfall meant that many village wells ran dry by January this year.

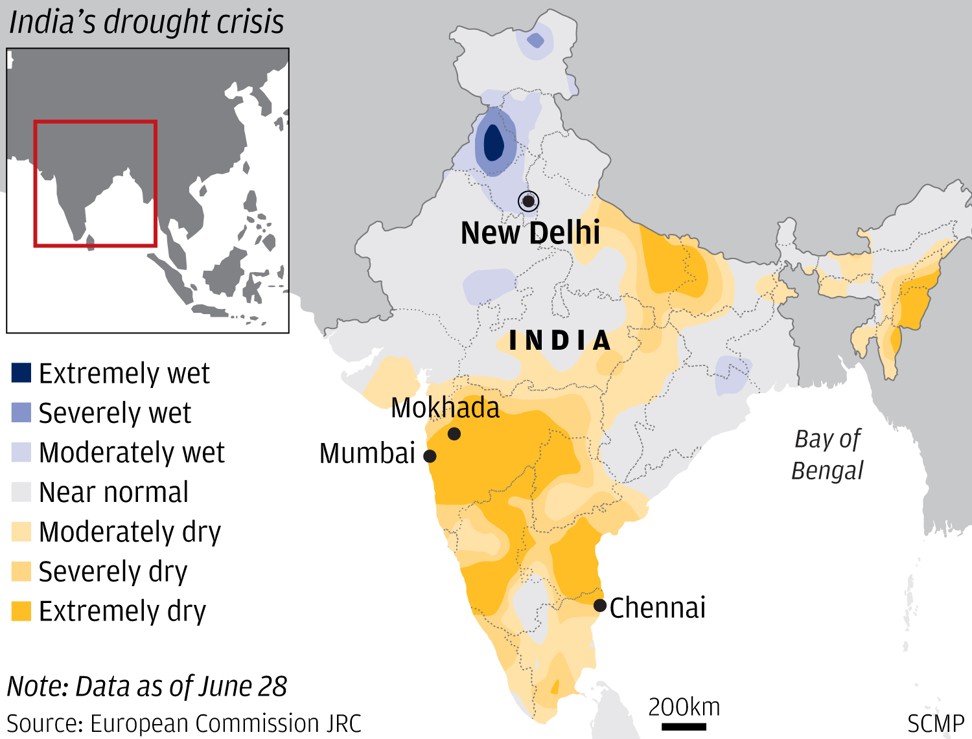

It isn’t just Palghar alone; 43 per cent of India is gripped by a severe drought, being abnormally to exceptionally dry.

Map of the areas facing drought in India. Graphic: SCMP

But Mokhada’s drought carries a heavy and almost tragic sense of irony. It is not a dry region; five rivers originate here. The region generally sees over 2,400 millimetres of rainfall a year. But instead of providing for the locals, much of the water is diverted to Mumbai – which gets a major chunk of its water from here – along with other cities and industrial corridors.

The scarcity can turn fatal. In April 2012, a woman died from the exertion of trying to fetch water. In addition, the hilly terrain in the region means the rainwater does not percolate but instead, slides off down the valley into the rivers.

Locals are left with the hard choice of staring at rivers flowing past, even as they struggle for each drop.

Mathura Waghare, a resident of Brahmanpada village in Mokhada, stands with a drum of water. Such drums cost as much as US$5-6. Photo: Kunal Purohit

SLEEPLESS NIGHTS SPENT DODGING SNAKES AND SCORPIONS

The crisis is overturning the lives of Mokhada locals, who are staying awake through the night in search of water.

Mathura Waghare, 35, from the tribal village of Brahmanpada, now has a routine that revolves around getting adequate water for her supply to survive each day.

The village’s only source of water, a common well, ran out of water in January this year. Since then, Waghare has been searching for water in nearby villages on foot. When she found water 2km away in a neighbouring village, she was relieved. But the next day, villagers there were up in arms.

“People in that village feared that they would run out of water if we continued going there. So, they refused to allow us to fill water,” she says.

That’s when Waghare decided that she had had enough. She decided to head into the forest, to a well she knew was a 45-minute walk from Brahmanpada. This did not have much water, but the groundwater area in the table was high, she said. So the villagers would wait at the well every day for groundwater to percolate into the well.

Each night at around 3am, Waghare starts walking into the forest with her stainless steel handis (large pots). Most nights, women from the neighbourhood walk with her. “It gets scary to walk alone. There are scorpions and snakes in the forest; the other night, we saw a snake slide past,” Waghare says.

Mathura Mavle dug this pit with her friend, using their bare hands, in their desperation for water. Photo: Kunal Purohit

With battery-operated torches in their hands, and balancing the handis on their heads, the women set out each night and sometimes, even multiple times in the day, if they receive unexpected guests or if the water runs out sooner. Once at the well, Waghare queues up, waiting for the water to percolate. “Sometimes, it takes 3-4 hours; other times, there is enough water in an hour. It is unpredictable,” she explains. Water filled, she balances two handis on her head, the third one in her hand, fingers firmly clasped around its neck.

On an average day, she sleeps for five hours, before waking up between 2am and 3am. But there are days when her worries are so severe that she cannot sleep.

“So, I finish my chores in the night and set out at 10pm or so. Without water, we can’t survive, so sleep does not matter,” she says.

TAKING MATTERS INTO HER OWN HANDS

Mathura Mavle, 30, sympathises with Waghare’s situation.

Mavle lives in the tribal village of Kharawali, about 5km away from Waghare’s Brahmanpada. Just outside Mavle’s house lies a well. But it is bone-dry and its floor lies exposed to the sun. Another well, 1.5km away, is also nearly dry.

So one summer day, two months ago, Mavle and Asha H* walked for a kilometre or so, climbing down small rocky cliffs to where a small stream flows past in the monsoons. The stream goes dry by October every year.

One rock at a time, they both dug a small hole in the earth, at the base of an old tree. They kept digging through the day. Seven hours later, at a depth of almost one metre, they hit water.

Warnings issued as temperatures pass 50 Celsius in India heatwave

The women have been trekking to the pit every day since, with their children and sometimes their husbands in tow, to collect water.But digging the hole, they realised, was just half the battle won. Standing over the pit, Mavle says: “There is only as much water a small pit like this can carry. So, whenever it runs out of water, we just sit around, waiting for groundwater to percolate into it.”

The unpredictability means locals can be queuing up at the pit for up to half the day. Today isn’t one of those days. Mavle walks into the pit, crouches and patiently fills her pots, one bowl at a time. “We got lucky today,” she says, smiling.

MOKHADA’S LONG-STANDING NEGLECT

For activists working in the region, Mokhada’s struggles are a result of a long-standing neglect of the region.

Brian Lobo, a veteran activist of the Kashtakari Sanghatana (Farmers Collective), says the locals have been clamouring for authorities to address the issue for years.

He points to the three major dams in the region – these dams on the Vaitarna river, flowing through the region, supplying daily over 1,000 million litres of water to Mumbai. “We have demanded that the water from one of these dams, the Upper Vaitarna dam in the region be used to fulfil the needs of locals, rather than being diverted for industrial purposes.”

Lobo said a study had even found it to be a workable solution. “But, consequent governments refused to implement it,” he said.

This crisis is not just about the poor management of water alone but a broader mismanagement of natural resources.

One of the first dams in the region, the Modak Sagar Dam, was constructed in 1957 to supply water to Mumbai. The dam supplies over 400 million litres of water to Mumbai each day.The administrative head of Palghar district, Dr Prashant Nanaware, admits that there’s a problem. He says the government is working out a solution. “We also believe that the river’s water can be diverted for locals. We are working on a proposal to have water supply schemes for these parched villages and once approved, we will execute these.”

But Mokhada is not alone in experiencing poor water supplies.

At a time when a severe water crisis has gripped much of India, including the southern metropolis of Chennai, such similar stories of poor management of water resources abound.

Workers told to shower less as reservoirs in Chennai city dry up

Chennai, a city with over 9 million inhabitants, faces a crippling water shortage – four major reservoirs that form the bulk of its water supply have dipped to less than 1 per cent of their capacity. Other sources are also running out of water. With its official monsoon season at least two more months away, the city is praying for unseasonal rainfall.But even in Chennai, data shows many of the city’s water bodies, which could have been a valuable asset in this scarcity, have become defunct due to poor management as well as allowing construction on it.

Similarly, unplanned urbanisation has led to many of its wetlands shrinking to a fraction of their original size in the last few decades.

Nityanand Jayaraman, a Chennai-based writer and a social activist who has been tracking environmental causes, says: “This crisis is not just about the poor management of water alone but a broader mismanagement of natural resources. Chennai’s growth has come at the cost of open spaces and water bodies, both of which are taken over and built upon to create more and more housing.”

The pattern isn’t unique to Chennai, Jayaraman says. Pointing to other Indian metros, he says: “Across different Indian metros, we have followed this same model of development, one that prioritises needs of housing and commerce but not the environment.”

*Name changed because she works for the local government and did not wish to be identified