The truth behind Occupy's rallying cry, "We are the 99%," was hard to forget, even for the people in both parties who dismissed the protesters as nothing more than naive college kids and envious poor people. From that point on, it was hard to ignore the data-backed fact that the gap between the top 1% of Americans and everyone else was larger than it had been since pre-Depression levels in the 1920s.

And as the decade progressed, researchers like the French economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman dug in and found that it was worse than expected. As they published in their 2018 World Inequality Report, the top 1% of American adults captured 20.2% of US national income in 2016, and the bottom 50% captured 12.5%. In 1980, the top 1% captured 11% of the national income, and the bottom 50% captured just over 20%.

Today, unemployment is at historically low levels, but wage growth has been painfully sluggish.

And so that means that even when the economy seems to be doing well, millions of Americans are still struggling. We're essentially in a new Gilded Age, referring to the period in the late 19th century of huge economic growth alongside massive inequality that followed Reconstruction.

Donald Trump addressed this sentiment on his path to the White House in the 2016 election, and his win also empowered a growing progressive wing in the Democratic Party.

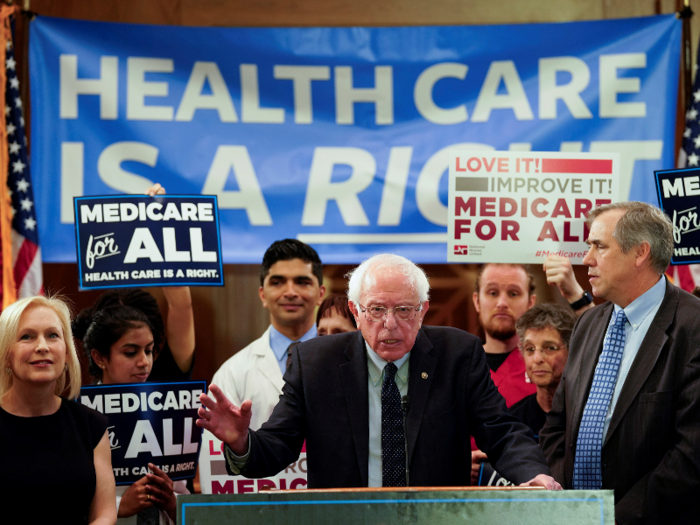

At this point, two ideas that were radical 10 years ago, a wealth tax on the assets of the richest Americans and Medicare for All, are pillars of both Sanders and Warrens' presidential platforms.

And while Trump's 2017 tax bill was traditionally conservative and far from populist, it included a policy for "opportunity zones" aimed at addressing inequality in parts of the country that weren't already bustling. Proposed by Republican Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina, the policy provides developers tax breaks as motivation for building them up. Though they have certainly not been without controversy, they've still received bipartisan support.

The 2010s saw the continuation of a fight between the left and right that had built steam in the aughts over climate-change policy. President Barack Obama signed the international Paris Agreement in 2016, setting targets for greenhouse emissions and regulation. However, Trump administration this year began the process of withdrawing from it.

But that hasn't stopped companies from moving forward with their own sustainability policies, even if done solely to get ahead of potential legislation from a possible Democratic administration.

Just over years ago, for example, outdoor apparel company and retailing giant Walmart formed an unlikely partnership through the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, an organization of about 250 members. These include some of the world's biggest brands, like Adidas, Disney, Gap, Levi's, Nike, and Target. The group created a sustainability index to measure the impact of apparel manufacturing, and 10,000 more manufacturers outside of the network now use the index.

Rose Marcario has been with Patagonia for 11 years, serving as CEO since 2013. In that time, she has made the company a champion of sustainability and shared its best practices with competitors.

She told Business Insider earlier this year that such partnerships are essential, regardless of who occupies the White House. "There's so much that we can do if we act collectively to fix these problems," she said. "I'm excited about it. But I do think that the next five, 10 years are the most absolutely critical for us to make serious change."

The financial crisis and rising inequality have both prompted a branch of left-leaning economists, like Nobel laureate Joe Stiglitz, to push back against the form of free market economics that has reigned for more than 40 years.

But while they are all calling for significantly increased taxes, even corporations with different interests are pushing back against one of the defining features of this era: the shareholder primacy theory.

The B Lab nonprofit, for example, has grown over the past decade to include 2,800 B Corporations (the b stands for benefit) and 8,000 legally registered benefit corporations. These companies have made commitments to creating value not only for shareholders, but for employees, customers, communities, and the environment. It started with brands like Patagonia and Ben & Jerry's, and has been gaining traction with giant multinationals, with the support of giant companies like Danone and Unilever.

And while it was not a binding document, the Business Roundtable's statement this year marked a significant recognition of the demands from employees and consumers for a new way of doing things. Companies like JPMorgan Chase and Mastercard have, over the past few years, been increasingly incorporating community-driven investments into their core business.

Peter Scher is JPMorgan's head of corporate responsibility and its DC branch, and oversees the international "AdvancingCities" philanthropic initiative. He told Business Insider that "we want to grow our business in these places and, ultimately, if we're going to grow the economy of a France or Michigan or the greater Washington region, you can't have all these economic hurdles holding people back."

The more companies want to influence communities, however, the more power corporations have over democratic institutions. It's one of the reasons why a call for renewed antitrust policy has emerged over the past several years for the first time since the 1980s.

The rise of Big Tech, namely Google, Facebook, and Amazon, has compelled progressives like Warren and Sanders to call for breaking up what they deem to be monopolies limiting healthy competition, but there has been a push from a smaller faction on the right as well.

Specifically, Republican Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, whose hero is the trust-buster Teddy Roosevelt, has made attacking concentrated corporate power his signature issue.

Matt Stoller, fellow at the progressive antitrust nonprofit the Open Markets Institute and author of "Goliath," told Business Insider that an alliance between the left and the right on this issue is not only necessary but very promising.

Over the past decade, seeds sown in the wake of the Great Recession have flowered even as Wall Street recovered and is doing as good as it ever has.

From democratic-socialists to conservative Republicans, from activists to CEOs, all with a variety of goals, there has been a growing recognition that today's capitalism is no longer working for enough Americans.

As voters and consumers, these Americans are now forcing the hands of politicians and executives to acknowledge their demands — and whether they know it or not, they're using a lot of the same language that protesters used almost 10 years ago.

And so if this past decade was about changing the conversation around capitalism, then the next decade will be about turning that rhetoric into action, regardless of who's president.

Stay tuned to Business Insider's Better Capitalism page throughout the month for an exploration of how this conversation has evolved, and how it's setting the stage for a new era.

I'm an interior designer. Here are 10 things in your living room you should get rid of.

I'm an interior designer. Here are 10 things in your living room you should get rid of. A software engineer shares the résumé he's used since college that got him a $500,000 job at Meta — plus offers at TikTok and LinkedIn

A software engineer shares the résumé he's used since college that got him a $500,000 job at Meta — plus offers at TikTok and LinkedIn A 101-year-old woman keeps getting mistaken for a baby on flights and says it's because American Airlines' booking system can't handle her age

A 101-year-old woman keeps getting mistaken for a baby on flights and says it's because American Airlines' booking system can't handle her age The Role of AI in Journalism

The Role of AI in Journalism

10 incredible Indian destinations for family summer holidays in 2024

10 incredible Indian destinations for family summer holidays in 2024

7 scenic Indian villages perfect for May escapes

7 scenic Indian villages perfect for May escapes

Copyright © 2024. Times Internet Limited. All rights reserved.For reprint rights. Times Syndication Service.